My first love was dance – and I spent about 15 years becoming quite good at it. My second love is rock climbing. And projecting is my jam. It makes sense, seeing as I replaced dance with climbing: learning and practicing a route is quite similar to learning and practicing a routine.

Here’s the interesting part: I was quite good at projecting right off the bat. I mean, I was giving projecting tips to my 5.13 climbing partner while I was working on first 5.12. That’s because I applied the skills that I learned in dance to my climbing projects.

So, I figured I should share some of these things to a wider audience in hopes that somebody else will get something out of all the years and tears I put into dance. I broke my toe and compacted the bone by wearing pointe shoes… and now I have two different-sized feet. Breaking in climbing shoes is the absolute worst. You’re welcome.

Work the crux until you can do it, then work it until you can’t not do it

If you watched Netflix’s Cheer, you probably heard coach Monica say something along these lines. Dance is no different, and neither is climbing: this is absolutely my philosophy for projecting. Let’s look at a real-life example: Hourglass, my first 12b.

My first session on the climb, I couldn’t do the crux. So far, so normal. My second session, I stuck it once. My third session, I could do it about one out of every three goes. Now, the crux is at the very end of this route. I mean, you climb 70 feet or so, clip the last draw, climb a bit more, and only then do you get to the crux. So a 33% success rate on this move in isolation just wasn’t going to work. Or, it might have worked, but it would have required a lot of time, luck, or both.

So, I worked that move until I stuck it almost every time, over and over again – and that only took me one more session. I probably did the crux 100 times in total. (NB: this was a dynamic step-up on slightly less than vert, which is a learned sort of movement that really benefits from repetition – not all cruxes need or should have 100 goes!) Then, I started redpoint goes from the beginning. I fell a couple of moves before the crux on my first go. Then, I fell at the crux twice. I sent fourth go.

That means I still managed to fall on that move after perfecting it in isolation: doing a single move or section is very different from doing a whole climb. That’s why it’s important to have the crux so dialed – if you’re only able to do it in isolation sometimes, how will you be able to do it in amongst the rest of the climb? And, more importantly, how much time and effort will it take?

I could have climbed that route over and over and fallen at the crux each go if I didn’t work the move to death. And that would have taken far more time than simply repeating the crux section. This is how you send things in a reasonable amount of time.

Math time

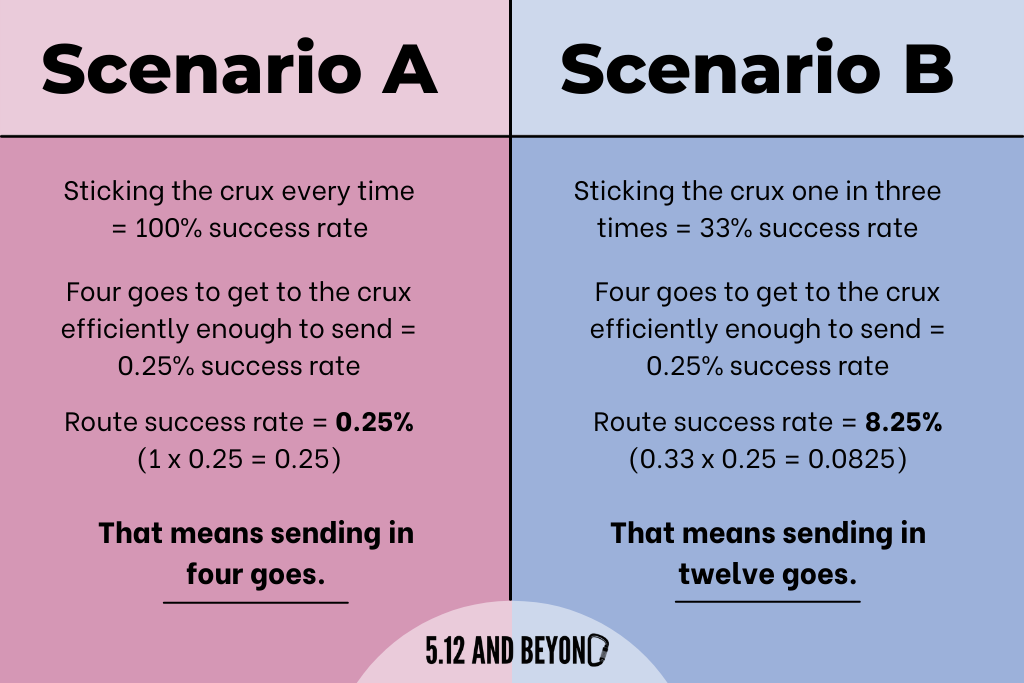

I’m going to show you some math now because numbers are cool and it will better illustrate this point. Let’s use my success rates to estimate how many goes I might have needed to send if I’d started putting in redpoint goes after I could do the move one in three times.

Now, I’m making some assumptions here (I would be learning to climb the route more efficiently each go, for one). But you get the point. I guarantee that working the crux for an extra session took far less time, energy, and skin than putting in 12 or so redpoint goes.

Working the crux vs. getting new high points

There’s another reason why working the crux works so well: you get super used to doing the moves while tired. That’s part of why breaking the climb into overlapping sections is good too, working toward high points and low points (if you don’t know, a low point is the lowest place where you can start climbing and make it to the chains – kind of an inverted high point). These are good techniques. I use them. But knowing that I can pull the crux when I’m dead tired is very helpful too.

See, when you go for high or low points, you’re working large sections of the climb equally – but parts of the climb are probably much harder than others. And harder things require more work. So going for a section-only approach is not the most efficient way to project.

Plus, pulling crux moves when you’re tired from working those very same moves gives you a different level of confidence that you can pull them from the ground. It’s more than the “oh, I can do this when I’m quite pumped” feeling you get from a high point: it’s “oh, I can do this when these very specific muscles that I’m putting through the wringer over and over are screaming at me to stop”.

In dance, you put on a shitty performance when you spend the whole time worrying about the hard bit at the end. Same with climbing: this leaves me free to be more present on my send goes, focusing on what I’m doing instead of worrying about the crux.

That said, there is such thing as too much working the crux: you don’t want to get injured or fatigue your crux muscles too much. Listen to your body, and stop working the move for the day when your performance starts to deteriorate.

Write down key crux information

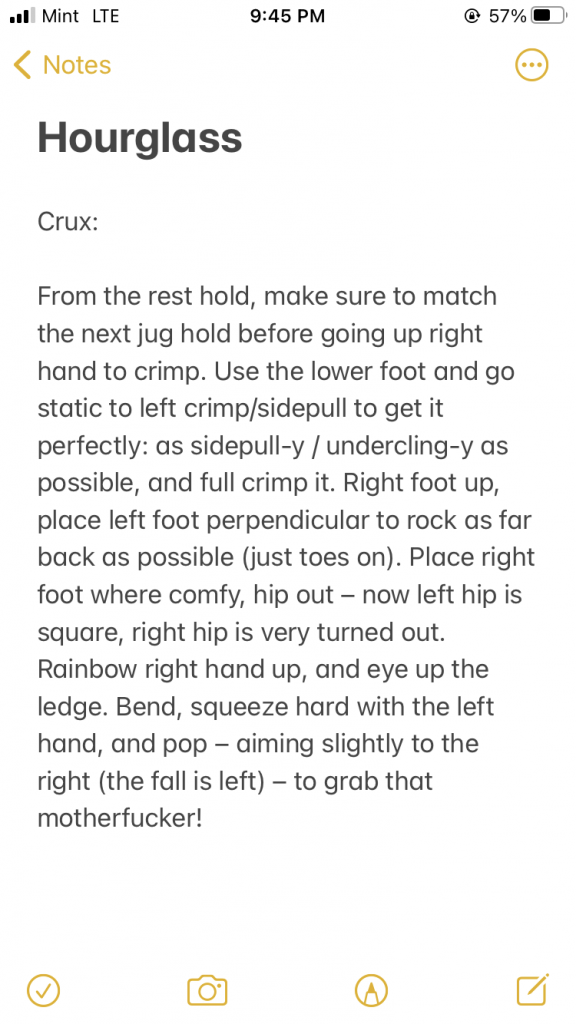

Once you figure out how to do the crux, write it down – and read it before every session. Better still, run through it in your head randomly when you’re doing the dishes or buying groceries. With dance, I used to do this all the time during class in high school. Suffice it to say, my teachers didn’t exactly love me. Here are my notes from the crux of Hourglass:

As you can see, it’s a mix of microbeta and what I like to call “internal beta”: where you think about a specific cue, like “squeeze hard with the left hand”. In dance, teachers will often give you these. “Hayley, when you turn, really think about spotting.” In climbing, you have to figure them out yourself – or, if you’re lucky, with the help of your climbing partner.

When you stick the move, think about what it was that you did and what advice you would give to another person attempting the climb. Write it down. These things are invaluable and often quite detailed – it’s really easy to forget a small part. “Use the lower foot and go static to left crimp/sidepull to get it perfectly: as sidepull-y / undercling-y as possible, and full crimp it.” This is quite complicated to just remember, and it’s only a third of what I wrote down…

So there you have it: a handful of projecting tips using strategies from dance. Not only have I tried and tested these, but I’ve seen them in various climbing courses and materials. I just came to them in a different way. This stuff works. So give it a go yourself and see what happens!

Featured image credit: Ryman Wiemann