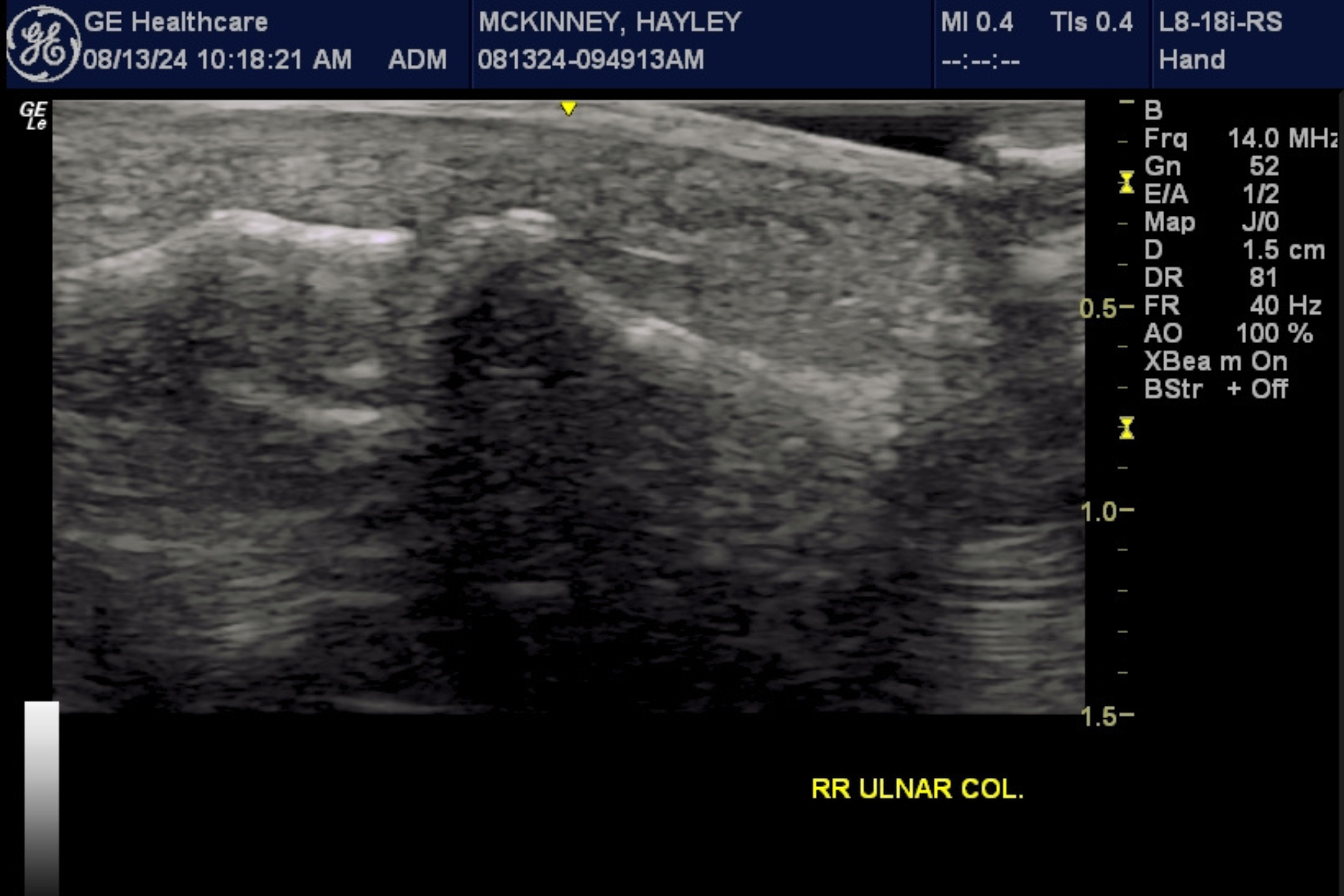

On May 19th, I broke my pinky toe running inside my apartment by clipping it on a door frame. Eleven weeks later, on August 3rd, I fell on the river crossing at Ten Sleep, giving myself a grade II ulnar collateral ligament sprain (right hand, ring finger, DIP joint). That means no climbing for another four weeks – plus the ten days between injury and diagnosis – on the back of five weeks without climbing thanks to the aforementioned broken toe.

If you follow me, you’ll know about all my toe. But this latest catastrophe is fresh. Am I the unluckiest person alive? Why do I keep getting hurt in ways that stop me from climbing… when I’m not even climbing? And – perhaps too introspectively – what does it all mean?

I fell forward into the river on all fours, perpendicular to the current. One minute, I was standing stationary on a dry rock protruding from the water, eyeing up my next move. The next, I was in the water, my feet having spontaneously lost friction. It came out of nowhere, like a dry fire.

The fall into the river was totally fine: no injuries. But as I got my bearings, the current pushed me – a sizable object with my sport climbing pack still strapped to my back – downstream. I fell again, deeper into the water, onto my right side. Only, my ring finger on my right hand didn’t come with me: it got jammed between two small rocks in the river bed, and what felt like molten lava flowed through it as the rest of my body twisted away. I yelped in pain.

Out of the river, my friends still on the other side, I rushed to the truck to change into dry clothes. It was cold and I was soaking wet. My friends arrived as I pulled a dry shirt on, having crossed the river far more successfully. I told them through gritted teeth that I was okay (I was) and that I might have hurt my finger (I did, although I didn’t know it yet).

The next 72 hours were spent resting, belaying, and just hanging out. I took ibuprofen around the clock and iced my finger three times a day, hoping that its bruised, swollen, and painful state was a just temporary blip. Aside from my symptoms in the actual finger itself, I felt totally fine – good, even – unlike other injuries. My HRV (if you know what that is), was at 89: close to an all-time high.

I can’t have hurt myself in a freak accident again. It’s probably just the inflammation. People jam and twist their fingers all the time.

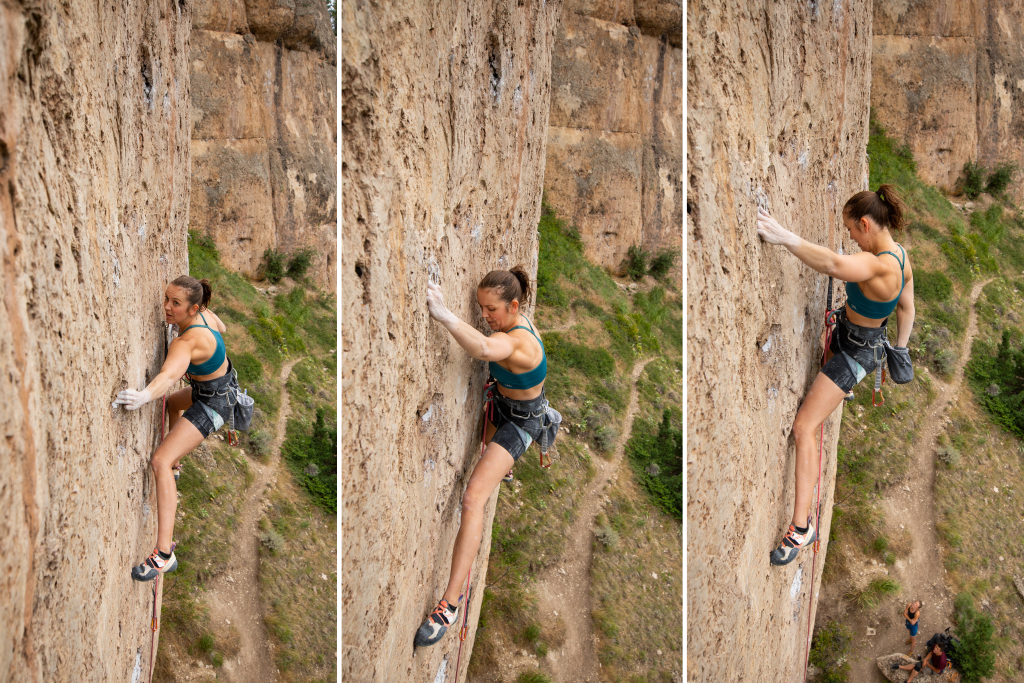

By the morning of day four, the swelling had gone down substantially. But the pain had evolved into something sharper and more sinister, concentrated in my DIP joint. Gentle manipulation hurt. I tried not to cry, but disobedient tears ran down my face regardless. The more time passed, the worse things looked. But ruthlessly (ignorantly?) optimistic, I requested a belay from a friend at Downpour Wall: home of gently overhanging jug hauls.

I warmed up on the hangboard, noticing what hurt, what didn’t, and what my body wouldn’t even allow me to try. I climbed the 5.11 warmup that I’d easily flashed a week prior, taking at the crux and downclimbing at the chains – unable to clip the anchor from the right-hand sidepull hero jug. I came down.

My climbing trip was over, even though it was just halfway through. My mindset changed from “I hope I can still climb on this trip” to “I hope I’m not out for six months”. I shifted focus to supporting my friends and enjoying the beautiful Wyoming wilderness.

My coach Jesse suggested I see Dr. Tyler Nelson remotely when I get home to Las Vegas. Realizing that I would be driving through Salt Lake City, where Tyler operates, I reached out and asked him if I would be worth making an in-person visit. He said yes, and – thanks to the kindness of my friends – I organized a place to stay in Salt Lake, confirmed the appointment, and booked a flight back to Vegas for afterward.

As I waited two days for the appointment, alone in my out-of-town friend’s beautiful and empty house, I felt… immensely grateful. Grateful to be able to go on climbing trips at all. Grateful for the three weeks of climbing that I had between my toe and finger injury, in which I onsighted my first 5.12. Grateful for my general good health, my friends, and my job that I love – one that has nothing to do with climbing and does not require an able body. Grateful for the flexibility and resources I have that allowed me to stay in Salt Lake and see a specialist.

Most of all, I felt grateful for my relationship with climbing. An older version of me would have been torn apart by staying in Ten Sleep injured and unable to climb. I would have had to leave. But this 34-year-old me thoroughly enjoyed my last week in Wyoming. I didn’t fill my extra time with work: rather, I slept in, hiked out to new crags, and supported my friends with encouragement, food, and limitless belays.

So no, I’m not the unluckiest person alive. Far from it: I am so very lucky. And I know, from experience, that the worst of times come before the best. There’s no sunshine without rain – and man, has it been pouring lately. (Between the toe and the finger, I also got really sick and I chipped a tooth eating popcorn in bed.) Whatever comes next is going to feel all the more sweet.

You can never know the counterfactual in your own life – what would have happened if I didn’t break my toe, or if I didn’t slip on the river crossing. But all in all, I’m doing okay. Better than okay, actually. As for why these things keep happening, it’s anybody’s guess – and it doesn’t really matter anyway. You can only play the hand you’re dealt, and mine is a good one – albeit a little beaten down right now.

That brings us to what does it all mean? Honestly, it’s a reminder that this is who I am: somebody who perseveres through adversity, big or small. I’ve lived in five different cities on three continents, packing up my life to start all over again with each move. I’ve left well-paying jobs to pursue writing professionally, with nothing but a creatively useless science degree and a deep well of passion. I’ve been married, I’ve been heartbroken, and I’ve been injured. I walked away from a potential dance career after nearly two decades of focused and hard work because it wasn’t serving me anymore.

That’s how I know that I want to climb, even through injury. Climbing brings me joy, community, athleticism, and purpose. It challenges me and – as twee as it sounds – it makes me a better person. And that’s a very powerful understanding to have: it’s a light at the end of the tunnel that never goes away.

When I was 24, living in Sweden, recently single and completely broke with nowhere to stay, I changed the lock screen on my phone to this: “if it were easy, everyone would be doing it”. Ten years later, the sentiment remains.

Featured image credit: Fallon Rowe